-

6e

CHAPTERIntrahepatic Cholestasis

Archith Boloor, Nikhil Kenny Thomas

ABSTRACT

Cholestasis is a symptom of many diseases, characterized by impaired bile formation or excretion. It can be intrahepatic or extrahepatic. Nonpregnancy-associated intrahepatic cholestasis, characterized by compromised liver flow, is discussed in this chapter, including its etiologies, clinical presentations, diagnostic methodologies, and therapeutic strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Cholestasis is not a disease, but a symptom of many diseases. Cholestasis appears when there is impaired formation or excretion of bile, and this can occur when the underlying disease process, acute or chronic, leads to impaired hepatobiliary function.

Cholestasis is subclassified into intrahepatic (hepatocyte injury, bile canaliculi, or intrahepatic bile ducts) or extrahepatic (extrahepatic ducts, the common hepatic duct, or the common bile duct).

Intrahepatic cholestasis, a condition characterized by compromised bile flow within the liver, manifests beyond pregnancy. Our article delves into the diverse etiologies, clinical presentations, diagnostic methodologies, and therapeutic strategies pertinent to nonpregnancy-associated intrahepatic cholestasis.

CLASSIFICATION

Two major categories of cholestatic disorders—(1) primary cholestatic liver diseases of genetic or unknown origin and (2) secondary cholestasis either due to hepatocellular injury (secondary intrahepatic cholestasis) (Box 1).

(IgG4: immunoglobulin G4; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease)

CAUSES OF CHOLESTASIS

Table 1 summarizes the causes of cholestasis.

TABLE 1: Causes of intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholestasis. Intrahepatic cholestasis

Extrahepatic cholestasis

• Viral hepatitis: Hepatitis B and C, hepatitis A, EBV, and CMV

• Alcoholic hepatitis

• NAFLD/MASLD

• Infiltrative diseases: TB, lymphoma, and amyloidosis

• Infections: Malaria, leptospirosis, and AIDS

• Drug-induced: Pure cholestasis (anabolic and contraceptive steroids) cholestatic hepatitis (chlorpromazine, erythromycin, and amoxiclav)

• Primary biliary cirrhosis

• Primary sclerosing cholangitis

• Sarcoidosis

• IgG4-related cholangitis

• Cystic fibrosis

• Inherited:

○ Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC)

○ Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC)

• Graft-versus-host disease

• Total parenteral nutrition

• Sepsis

• Paraneoplastic syndrome

• Veno-occlusive disease

• Choledocholithiasis

• Bile duct tumors

• Pancreatic carcinoma

• Mirizzi’s syndrome

• HIV-associated cholangiopathy

• Parasites

(CMV: Cytomegalovirus; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IgG4: immunoglobulin G4; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; MAFLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; TB: tuberculosis) Chronic alcohol consumption triggers hepatocellular injury, disrupting bile canaliculi and causing intrahepatic cholestasis. Intrahepatic biliary radicles are compressed and the permeability of the bile ductules is increased in alcohol-induced cholestasis.

The pandemic on the rise of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is also associated with mild cholestasis, however, severe cholestatic features such as bile duct damage and loss are rare in metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD); unless there is a coexistence of other liver diseases.

Hepatitis B and C infections induce hepatocellular inflammation, affecting bile excretion and leading to cholestasis. In our country, tropical infections such as leptospirosis and malaria are also to be considered.

Drug-induced cholestasis-hepatotoxic drugs (e.g., macrolide antibiotics, carbamazepine, anabolic steroids, terbinafine, haloperidol, and phenothiazines) interfere with hepatocellular transporters and cause intrahepatic bile stasis. Many alternative medications and substances, (kava, senna, greater celandine, and black cohosh) can cause liver injury and cholestasis.

Gallstones obstructing intrahepatic bile ducts impede bile flow and instigate cholestasis.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) occurs in the late second and early third trimester of pregnancy with an incidence rate is between 0.2 and 2% of the pregnancies. Studies have shown an association of ICP with increased fetal complications, such as spontaneous preterm birth and sudden intrauterine demise.

Granulomatous hepatitis occurs in association with infections (tuberculosis and schistosomiasis), systemic diseases (sarcoidosis), or drugs are associated with cholestasis. Only histopathology confirms this entity.

Primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and IgG4-mediated cholangitis are autoimmune-mediated diseases resulting in bile duct inflammation, fibrosis, and bile flow obstruction.

Genetic mutations affecting bile transporters (e.g., ABCB11) lead to the development of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) and benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC). Childhood diseases such as Byler disease, are usually fatal; but in patients with syndromic paucity of the ducts (Alagille syndrome), the prognosis is much better.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The symptoms and signs are variable and range from none to intractable pruritis. Subtle Clinical features of cholestasis include fatigue and itching all over the skin. Jaundice, a hallmark of cholestasis, results from elevated bilirubin levels. Pruritus, driven by an accumulation of bile salts within the skin, presents as a distressing symptom. Acholic stools and dark urine reflect bilirubin excretion impairment. Abdominal discomfort and hepatomegaly arise due to bile stasis and hepatocellular congestion. Systemic fatigue, attributed to hindered bile metabolism, contributes to patient debilitation. The symptoms and signs of the etiological causes may sometimes predominate.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACHES

Laboratory Investigations

Elevated bilirubin levels, increased alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) indicate cholestasis. The simultaneous elevation of ALP and GGT (0.5–2.5 times the upper normal limit or 60–300 U/L and 19–95 U/L, respectively) strongly suggests a cholestatic condition.

Imaging Modalities

Ultrasonography is a simple, low-cost, easily available, and noninvasive test that allows easy identification of extrahepatic dilatation of the biliary tree. Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (Fig. 1) are better to reveal hepatic morphology and potential obstructions.

FIG. 1: ERCP—cholangiogram showing a dilated CBD seen in extrahepatic cholestasis.

(CBD: common bile duct; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography)

All patients with suspected intrahepatic cholestasis must undergo screening for viral hepatitis [hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)], drug/toxin screening, and immunological screening with antimitochondrial antibodies (AMAs) and other antibodies (IgG4, ANA, pANCA, anti-M2, anti-gp120, and anti-sp100).

Liver biopsy assists in identifying inflammation, fibrosis, and alterations in bile duct architecture. The decision to perform a liver biopsy is based on several factors, such as the patient’s age, blood investigations, treatment options, and prognosis.

DIAGNOSTIC ALGORITHM

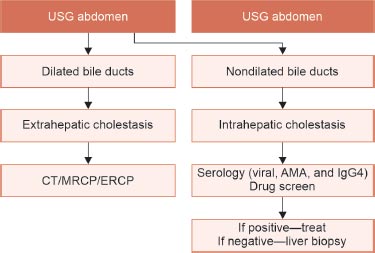

Flowchart 1 explains the diagnostic process.

FLOWCHART 1: Algorithm for diagnostic.

(AMA: apical membrane antigen; CT: computed tomography; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; IgG4: immunoglobulin G4; MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; USG: ultrasound)

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Pharmacotherapy

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) ameliorates bile composition and flow, a cornerstone treatment. Obeticholic acid, which is an agonist of the nuclear receptor farnesoid X receptor (FXR) (5–10 mg/day) has been tried in patients with PSC. S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) has been tried in the treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and drug-induced cholestasis.

Lifestyle modifications such as abstinence from alcohol and cessation of hepatotoxic medications are essential. Antihistamines and bile acid sequestrants, such as cholestyramine, rifampicin, naltrexone, and sertraline mitigate pruritus. Ultraviolet irradiation, albumin dialysis, or nasobiliary drainage if the other treatments for refractory pruritus endoscopic interventions: ERCP and percutaneous approaches address gallstone-related cholestasis. Immunosuppression manages autoimmune-mediated cholestasis, particularly primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC). Calcium, vitamin D, and fat-soluble vitamin supplementations are recommended in chronic cholestasis.

Liver transplantation must be considered if the active medical treatments for cholestatic liver disease are unsuccessful, or if the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score is 15 or more, or if there is rapid deterioration.

CONCLUSION

Intrahepatic cholestasis is a condition where the flow of bile from the liver is impaired. While it is commonly associated with pregnancy, it can also occur outside of pregnancy. Nonpregnancy-associated intrahepatic cholestasis manifests via diverse etiologies, necessitating a comprehensive approach for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

SUGGESTED READINGS

1. Sticova E, Jirsa M, Pawłowska J. New Insights in Genetic Cholestasis: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:2313675.

2. Lu L; Chinese Society of Hepatology and Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for the Management of Cholestatic Liver Diseases (2021). J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022;10(4):757-69.

3. Beuers U, Hohenester S, de Buy Wenniger LJ, Kremer AE, Jansen PL, Elferink RP. The biliary HCO(3)(-) umbrella: a unifying hypothesis on pathogenetic and therapeutic aspects of fibrosing cholangiopathies. Hepatology. 2010;52(4):1489-96.

4. Onofrio FQ, Hirschfield GM. The Pathophysiology of Cholestasis and Its Relevance to Clinical Practice. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2020;15(3):110-4.

Home

Home

e-Contents

Chapter 1e: Prosthetic Valve Thrombosis

Harbir Kaur Rao, Rajinder Singh GuptaChapter 2e: Diabesity and Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

Rajiv Awasthi, Avivar AwasthiChapter 4e: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: An Update

Vinay Kumar Meena, Nazim Hussain, Rajani NawalChapter 5e: Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors Beyond Glycemia

Amit VarmaChapter 6e: Intrahepatic Cholestasis

Archith Boloor, Nikhil Kenny ThomasChapter 8e: Tobacco and Chest

Rajbir Singh, Prabhpreet Kaur, BL Bhardwaj, RS BhatiaChapter 9e: Lung Metastasis

RS Bhatia, Prabhpreet Kaur, Rajbir Singh, BL BhardwajChapter 10e: Important Drug Interactions in Clinical Practice

Srirang AbkariChapter 11e: Renal Tubular Acidosis

Surjit TarafdarChapter 12e: Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease

Saif Quaiser, Ruhi Khan, Shahzad Faizul HaqueChapter 14e: Current Positioning of Nonstatin Therapy of Dyslipidemia

Saumitra Ray, Srina RayChapter 15e: How to Deal with Complication of Prolonged Antibiotic Therapy

Pushpita MandalChapter 16e: Navigating End-of-life Medical Decisions with Cultural Sensitivity

Reinold OB GansChapter 17e: Osteocalcin: New Frontiers in Diabetes

Sudha Vidyasagar, Avinash HollaChapter 18e: Arterial Blood Gas Analysis: A Rational Approach

SV Ramanamurty, TVSP MurtyChapter 19e: Asthma: New Therapeutic Avenues

Sachin Hosakatti