-

18e

CHAPTERArterial Blood Gas Analysis: A Rational Approach

SV Ramanamurty, TVSP Murty

ABSTRACT

In day-to-day clinical practice, especially in emergency wards, clinicians often encounter critically ill patients, with respiratory failure or acid–base or electrolyte disturbances.

It will be prudent for the treating physician to order for arterial blood gas (ABG) test at the earliest. By analyzing the ABG report, one can determine whether there is type 1 or type 2 respiratory failure or any acid–base disorder.

Acid–base disorders include metabolic acidosis, respiratory acidosis, metabolic alkalosis, or respiratory alkalosis. An acid–base disorder may be primary, compensated partially or fully. Sometimes, mixed acid–base disorders can exist wherein there will be no compensation. A systematic approach to the analysis of ABG report will unravel the situation so that the concerned physician can manage properly.

INTRODUCTION

Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis is one of the crucial investigations which are most frequently employed in a critical care setting. A structured approach to rational interpretation of the ABG report requires a clear understanding of the basic concepts.

HISTORICAL ASPECTS

History of development of blood gas analysis and its application probably dates back to the pioneering work of anesthesiologist and researcher Dr John Severinghaus. In the 1950s, he developed the Stow–Severinghaus-type carbon dioxide electrode, which continues to be used for measurement of pCO2 in blood gas machines today and the first-ever three-function (pH, pCO2, and pO2) blood gas analyzer (Fig. 1).

PURPOSE OF ARTERIAL BLOOD GAS

Arterial blood gas testing is widely used in emergency departments to evaluate the sick patients for metabolic disorders (acid–base disorders) and respiratory status, i.e., oxygenation and ventilation.

BACKGROUND

- The concept of pH was first put forward by the Danish chemist Soren Peter Sørensen 1909 to refer to the negative logarithm of hydrogen ion concentration (H+).

- The pH is a measurement of the acidity or alkalinity of the blood.

- The term “pH” stands for “Potential for Hydrogen”.

- Plasma pH of 7.40 corresponds to H+ ion concentration of 40 nEq/L.

- Plasma H+ ion concentration is inversely proportional to pH (Table 1).

- In 1908, Lawrence Joseph Henderson wrote an equation describing the use of carbonic acid as a buffer solution.

- Later, Karl Albert Hasselbalch re-expressed that formula in logarithmic terms, resulting in the so-called Henderson–Hasselbalch equation.

H+ (nEq/L) = 24 × [(PaCO2/HCO3)]

FIGS. 1A AND B: John W Severinghaus, MD, who invented modern blood gas analysis by combining electrodes for carbon dioxide, oxygen, and pH into one machine, died on June 2 at the age of 99 years.

TABLE 1: Relationship between plasma pH and H+ ion concentration. pH

[H+] (nEq/L)

6.8

158

6.9

125

7.0

100

7.1

79

7.2

63

7.3

50

7.4

40

7.5

31

7.6

25

7.7

20

7.8

15

COMPONENTS OF ARTERIAL BLOOD GAS

- pH (7.35–7.45) [Measurement of acidity or alkalinity, based on the hydrogen (H+) ions present]

- PaO2 (80–100 mm Hg) (Partial pressure of oxygen that is dissolved in arterial blood)

- SaO2 (95–100%) (Arterial oxygen saturation)

- PaCO2 (35–45 mm Hg) (Amount of carbon dioxide dissolved in arterial blood)

- HCO3 actual (22–28 mEq/L) (Actual bicarbonate: Plasma bicarbonate concentration, calculated from the actual pCO2 and pH measurements)

- HCO3 standard (22–28 mEq/L) (Standard bicarbonate: Plasma bicarbonate concentration calculated from the pCO2 and pH measurements in the arterial blood sample after the pCO2 is corrected)

- Base excess (BE; −2 to +2) (BE indicates the amount of excess or insufficient level of bicarbonate in the system)

- Na (135–145 mEq/L) (Plasma sodium concentration)

- K (3.5–5 mEq/L) (Plasma potassium concentration)

- Cl (95–105 mEq/L) (Plasma chloride concentration)

- Ca (1.0–1.25 mEq/L) (Plasma ionized calcium concentration)

- Lactate (0.4–1.4 mEq/L) (Lactate is produced as a by-product of anaerobic respiration. It is a good indicator of poor tissue perfusion.)

- Hemoglobin (Hb) (13–18 g/dL for men, 11.5–16 g/dL for women)

PHYSIOLOGICAL ASPECTS

Note: Gas molecules diffuse from higher partial pressures to lower partial pressures

- Alveolar oxygen (O2) Pressure > Pulmonary capillaries

- Pulmonary capillary carbon dioxide (CO2) Pressure > alveolar pressure

Hence,

- O2 moves from alveoli into pulmonary capillaries (oxygenation)

- CO2 diffuses from pulmonary capillaries into alveoli (ventilation)

TERMINOLOGY

- Type 1 respiratory impairment is defined by low PaO2 with normal or low PaCO2 due to inadequate oxygenation

- With PaO2 (mm Hg): Mild: 60–79, moderate: 40–59, severe: <40

- Causes: Pneumonia, acute asthma, pulmonary embolism, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pneumothorax, etc.

It is better to explain it in terms of FiO2 provided.

Managed with treatment of the cause

Support with mechanical ventilator, increase FiO2

- Type 2 respiratory impairment is defined by high PaCO2 (hypercapnia) > 45 mm Hg.

- Acute rises in PaCO2 lead to dangerous accumulation of acid in the blood and must be reversed earliest.

- Cause: Acute hypoxia

- Chronic hypercapnia is accompanied by a rise in the bicarbonate level, which preserves acid–base balance

- Causes: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), opiate or benzodiazepine toxicity, inhaled foreign body, flail chest, neuromuscular disorders, obstructive sleep apnea

- Acute rises in PaCO2 lead to dangerous accumulation of acid in the blood and must be reversed earliest.

Note:

- Whenever there is a change in hydrogen ion concentration due to a change in PaCO2, it is called respiratory acid–base disturbance.

- With high PaCO2, it is called respiratory acidosis.

- With low PaCO2, it is called respiratory alkalosis.

- Whenever there is a change in hydrogen ion concentration due to a change in HCO3, it is called metabolic acid–base disorder.

- With low HCO3, it is called metabolic acidosis.

- With high HCO3, it is called metabolic alkalosis.

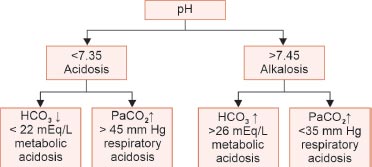

- Acidosis

- When pH < 7.35 (due to increase in acid or decrease in alkali)

- Metabolic acidosis: pH < 7.35 and HCO3 < 22 mEq/L

- Respiratory acidosis: pH < 7.35 and PaCO2 > 45 mEq/L

- When pH < 7.35 (due to increase in acid or decrease in alkali)

- Alkalosis

- When pH > 7.45 (due to decrease in acid or increase in alkali)

- Metabolic alkalosis: pH > 7.45 and HCO3 > 26 mEq/L

- Respiratory alkalosis: pH > 7.45 and PaCO2 < 35 mm Hg

- When pH > 7.45 (due to decrease in acid or increase in alkali)

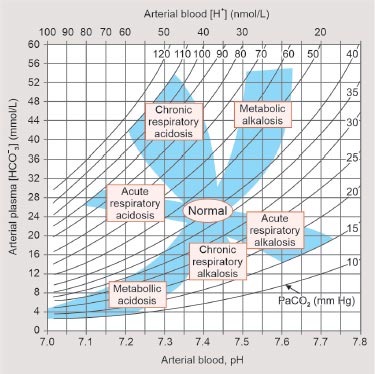

Note: Alternatively, the nature of the acid–base disorder can be determined by using ABG nomogram (Fig. 2).

PHYSIOLOGICAL COMPENSATION

Compensation takes place by the buffering systems in the body.

FIG. 2: An alternative way of interpreting arterial blood gas (ABG) by utilizing ABG nomogram.

Source: Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Jameson J, Loscalzo J. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 18th edition. New York: McGraw Hill; 2011.

TABLE 2: Compensatory response to simple/primary acid–base disorders. Primary acid–base disorders

Compensation

Metabolic acidosis (pH↓, HCO3↓)

• PaCO2 gets low, i.e., moves in the same direction

• PaCO2 = [(1.5 × HCO3) + 8]2 or

• PaCO2 = HCO3 + 15

Metabolic alkalosis (pH↑, HCO3↑)

PaCO2 = 0.75 mm Hg rise per mEq/L rise in HCO3

Respiratory alkalosis (pH↑, PaCO2↓)

• Acute: HCO3 will fall by 0.2 mEq/L per mm Hg fall in PaCO2

• Chronic: HCO3 will fall by 0.4 mEq/L per mm Hg fall in PaCO2

Respiratory acidosis (pH↓, PaCO2↑)

• Acute: HCO3 will rise by 0.1 mEq/L per mm Hg rise in PaCO2

• Chronic: HCO3 will rise by 0.4 mEq/L per mmHg rise in PaCO2

Note: During compensation, HCO3 and PaCO2 move in the same direction. Compensatory Response to Simple/Primary Acid–Base Disorders

Refer to Table 2.

Note:

- During compensation, HCO3 and PaCO2 move in the same direction.

- If they move in the opposite direction, mixed acid–base disorder should be suspected.

TABLE 3: Common mixed acid–base disorders. Disorders

Common causes

Metabolic acidosis and respiratory acidosis

DKA

Shock with respiratory failure

Metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis

Liver failure

Salicylates poisoning

Respiratory acidosis and metabolic alkalosis

COPD on diuretics

Metabolic acidosis and metabolic alkalosis

DKA with vomiting

Metabolic alkalosis and respiratory alkalosis

• Liver failure with vomiting

• Patient on ventilator with continuous nasogastric aspiration

(COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DKA: diabetic ketoacidosis)

FIG. 3: Male 45 years, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with sepsis, metabolic acidosis. pH 7.286, PaO2 77.43, PaCO2 15.92, HCO3 7.22, BE 19.4 mmol/L, lactate 1.53, Cl 122.1 mmol/L.

Diagnosis: Mixed disorder: Metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis

Type 1 respiratory failureMixed Acid–Base Disorders (Table 3; Figs. 3 to 7)

Mixed acid–base disorder is defined as independent coexistence of more than one primary acid–base disorder.

How to suspect mixed acid–base disorders?

- Mixed acid–base disorders occur in critically ill patients.

- Check the direction of changes, which take place in the opposite direction.

FIG. 4: Female 47 years, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), with lupus nephritis with dyspnea, metabolic acidosis + respiratory acidosis + treated with dialysis and mechanical ventilation. pH 7.119, PaCO2 19.3, PaO2 279.8 on FiO2 15 L, HCO3 6.1, BE 21.4 mEq/L.

Day 2: pH 7.228, PaO2 353 on ventilator, HCO3 11.8 mEq/L, BE 14.4 mEq/L, PaCO2 29.3

Diagnosis: Mixed acid–base disorder with metabolic acidosis and respiratory acidosis

FIG. 5: Female 24 years, ILD with ARDS, type 1 ARF with FiO2 60%, tidal volume 380 mL PEEP 5 cm, respiratory rate 16 breath/min, pH 7.358, PaCO2 53.40, PO2 95.21, VA/C mode, HCO3 27.01, BE 1.86 mEq/L.

Diagnosis: Acute respiratory acidosis with hypoventilation

(ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARF acute respiratory failure; ILD: interstitial lung diseases)

FIG. 6: Female 52 years, diabetes mellitus, sepsis, nephropathy, hypoproteinemia, anion gap metabolic acidosis, with respiratory acidosis (mixed acid–base disorder, lactic acidosis) on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). pH 7.213, PaCO2 41.14, PaO2 140.5 at 50% FiO2, SO2 98.82%, HCO3 14.62, Hb 11.9 g/dL, lactate 4.32, Na 140, K 3.9, blood urea 65 mg/dL, serum creatinine 3.6 mg, Blood sugar 208 mg/dL, albumin 2.2 g/dL, total leukocyte count (TLC) 16,6000/cmm, urine albumin ++, urine sugar +++, temperature 99.8οC, BP 100/60 mm Hg, RR 26, PR 115, AG = 140 – (110.8 + 14.62) =15 mEq/L. In view of albumin 2.2 g/L, add 2.5 × 2 = 5 to AG. So, AG = 15 + 5 = 20.

Expected PaCO2 = 14.62 + 15 = 29.62, but measured value = 41.14.

Diagnosis: Mixed acid–base disorder with metabolic acidosis and respiratory acidosis.- Compare expected compensation with measured value. If the measured value is either high or low, suspect mixed acid–base disorder.

- Check the anion gap. In certain acid–base disorders, almost all values may be in the normal range. Only the anion gap will clinch the diagnosis of a mixed disorder.

- Physiological compensation does not take place in case of mixed acid–base disorders.

APPROACH FOR EVALUATION OF ARTERIAL BLOOD GAS

There are three important approaches for evaluation of acid–base disorders:

- Physiological or Boston approach (developed by Schwartz and Relman from Boston)

- Base excess or Copenhagen approach

- Physicochemical or the strong ion approach/strong ion difference (SID)—Stewart’s approach

FIG. 7: Male 41 years, decompensated chronic liver disease, portal hypertension, right massive pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, acute kidney injury (AKI), hepatic encephalopathy. pH 7.45, PCO2 26.69 mm Hg, HCO3 15.81, BE −7.24 mEq/L

Measured PCO2 is 26.69 mm Hg, lower than expected value.

Hence, mixed acid–base disturbance—metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis.Clinical Approach

- Take targeted history in all critically ill patients followed by quick but meticulous clinical examination.

- Arterial blood sample to be taken, observing all precautions, preferably by observing modified Allen test, if acid–base disorder or respiratory impairment is suspected.

- To know the normal values of different components of ABG

- Validate the ABG report.

- Analyze the ABG report and validate as below:

- pH indirectly signifies hydrogen ion concentration

- By the rule of thumb, if pH is 7.40, subtract the two numbers after 7 in the pH from 80, i.e., H+ = 80 − 40 = 40 (A).

- H+ ion concentration = 24 × PaCO2/HCO3

- Hence, H+ = 40 = 24 × 40/24 = 40 (B).

- Compare the H+ by the two methods (validated if both results match).

- Assess oxygenation and ventilation—PaO2, SaO2, PaCO2

- Look at PaO2/FiO2 ratio.

- Normally, the ratio is 1:400–1:500.

- If the ratio is < 1:300, consider ARDS.

- Whether there is hypoventilation or hyperventilation by looking into PaCO2

- Look at pH, whether acidemia or alkalemia

- Assess primary acid–base disorder (Flowchart 1)

- Assess whether the disorder is acute or chronic; if the primary disorder is respiratory, consider the history of the patient.

- Assess the compensatory response.

- Determine whether there is any mixed acid–base disorder.

- Analyze the ABG report and validate as below:

FLOWCHART 1: Primary acid–base disorders.

SOME IMPORTANT “ACID–BASE DISORDERS”

Metabolic Acidosis

Metabolic acidosis is characterized by fall in plasma HCO3 and fall in pH below 7.35. The PaCO2 is secondarily reduced by hyperventilation, thus minimizing the fall in pH.

Mechanisms

- Loss of HCO3 through kidney (type 2 renal tubular acidosis) or through gastrointestinal (GI) tract (diarrhea). Excess production of metabolic acids either by endogenous addition like DKA or by exogenous addition like silicate or ammonium chloride poisoning or decreased renal excretion like chronic kidney disease

Clinical Features

- Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, Kussmaul’s breathing, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, headache, confusion, and drowsiness

- May be normal anion gap or high anion gap—metabolic acidosis

Management

- Underlying primary cause to be treated

- IV fluids, insulin, and electrolyte replacement necessary for DKA

- Administration of sodium bicarbonate and/or dialysis in case acidosis associated with renal failure

- Restoration of an adequate intravascular volume and peripheral perfusion are necessary in lactic acidosis.

Note:

The following principles are to be adhered to:

- If pH is <7.15 or base excess is −12 or more, administer sodium bicarbonate as infusion.

- The goal is to keep pH between 7.1 and 7.15.

- Dose of sodium bicarbonate required depends on the volume of distribution of HCO3.

- Between pH 7.3 and 7.4, distribution space is 50% of the lean body weight.

- Amount of HCO3 required =

(Desired HCO3 − actual HCO3) × 0.5 body weight in kg

- If the pH is <7.1, volume of distribution is 100% of the lean body weight

(Desired HCO3 − actual HCO3) × body weight in kg

- 50% of the requirement has to be given in the first 24 hours, preferably as IV infusion but not as bolus

- The remaining dose is to be given considering the pH on the second day.

Respiratory Acidosis

Respiratory acidosis is a clinical disorder characterized by an elevation in paCO2 (hypercapnia) leading to reduction in pH and variable compensatory increase in the plasma HCO3.

- It may be acute: With a duration of < 24 hours or chronic > 24 hours

Mechanisms

Airway obstruction, pulmonary disease, muscle fatigue, or abnormality in ventilator control

Clinical Features

- Those of the underlying cause and those due to hypercapnia

- Acute severe respiratory acidosis may cause anxiety, headache, dyspnea, confusion, psychosis, hallucination, and coma.

- Mild-to-moderate chronic hypercapnia may cause sleep disturbances, loss of memory, personality changes, tremor, and myoclonic jerks.

Treatment

- Treatment varies as per the severity, rate of onset, and underlying etiology.

- Acute hypercapnia: Mechanical ventilatory support; increase the positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), FiO2, tidal volume, and set respiratory rate in order to keep the airways and alveoli patent.

- Target PaCO2 level would be 40 mm Hg.

- Chronic hypercapnia O2 therapy should be administered cautiously, aiming for the lowest possible concentration, with the target PaCO2 level being lower than the previously stable value.

Note:

- Avoid alkali therapy except in patients with associated metabolic acidosis or severe acidosis (pH < 7.15) or severe bronchospasm.

Metabolic Alkalosis

- The primary abnormality in the bicarbonate buffering system is a rise in HCO3.

- There is little compensatory change in PaCO2.

- It is less common than metabolic acidosis.

- It is characterized by increase in plasma bicarbonate, rise in pH, and small compensatory rise in PaCO2.

Causes

- Vomiting or gastric aspiration, diuretic use (thiazides, furosemide), hypokalemia, primary and secondary hyperaldosteronism, administration of exogenous alkali

Clinical Features

- Acute alkalosis may cause tetany, confusion, and drowsiness.

Treatment

- Treatment of the underlying cause in saline responsive alkalosis

- IV isotonic saline with KCl or Isolyte G are preferred infusions.

- Avoid H2 receptor inhibitors, proton-pump inhibitors, and exogenous alkali.

- Dialysis may be helpful in occasional patients with severe metabolic alkalosis.

Respiratory Alkalosis

It is characterized by low PaCO2 (<35 mm Hg) and (high pH > 7.45) and compensatory low HCO3.

Etiology

- Normal pregnancy, high altitude residence

- Anxiety- or pain-induced hyperventilation

- Sepsis or hepatic failure or brain tumor

- Excessive mechanical ventilator support

Clinical Features

- They vary with severity, rate of onset, and underlying disorders.

- Light headache, tingling of the extremities, circumoral numbness, cardiac arrhythmias, rarely seizures.

Treatment

- Vigorous treatment of the underlying cause

- O2 supplementation to combat hypoxemia

- Reassurance and rebreathing into paper bag if the cause is psychogenic

- Pretreatment with acetazolamide minimizes symptoms due to hyperventilation at high altitude

CONCLUSION

Respiratory impairment or acid–base disturbances can occusr in different clinical settings, such as obstetric practice, intraoperative or postoperative conditions, road traffic accidents, sepsis, or many critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). Hence, a high index of clinical suspicion is required to predict the proper clinical condition and ABG should be ordered as early as possible and carefully analyzed and managed accordingly.

SUGGESTED READINGS

1. Severinghaus JW. Gadgeteeriing for health care. Anaesthesiology. 2009;110:721-8.

2. Sorensen SPL. Enzyme studies II. The measurement and meaning of hydrogen ion concentration in enzymatic processes. Biochemishe Zeitschrift. 1909;21:131-200

3. Encyclopedia Britannica. [online] “Henderson–Hasselbalch equation” biochemistry. Available from https://www.britannica.com/science/Henderson-Hasselbach-equation [Last accessed January, 2024].

4. Acid–Base Tutorial. Acid–base tutorial—history. [online] “Henderson–Hasselbalch equation” biochemistry. Available from [Last accessed January, 2024].

5. Muller-Plathe O. A monogram for the interpretation of acid-base data. J Clin chem. Clin Biochem. 1987;25(11):795-8.

6. Kraut JA, Madias NE. Metabolic acidosis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6:274-85.

Home

Home

e-Contents

Chapter 1e: Prosthetic Valve Thrombosis

Harbir Kaur Rao, Rajinder Singh GuptaChapter 2e: Diabesity and Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

Rajiv Awasthi, Avivar AwasthiChapter 4e: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: An Update

Vinay Kumar Meena, Nazim Hussain, Rajani NawalChapter 5e: Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors Beyond Glycemia

Amit VarmaChapter 6e: Intrahepatic Cholestasis

Archith Boloor, Nikhil Kenny ThomasChapter 8e: Tobacco and Chest

Rajbir Singh, Prabhpreet Kaur, BL Bhardwaj, RS BhatiaChapter 9e: Lung Metastasis

RS Bhatia, Prabhpreet Kaur, Rajbir Singh, BL BhardwajChapter 10e: Important Drug Interactions in Clinical Practice

Srirang AbkariChapter 11e: Renal Tubular Acidosis

Surjit TarafdarChapter 12e: Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease

Saif Quaiser, Ruhi Khan, Shahzad Faizul HaqueChapter 14e: Current Positioning of Nonstatin Therapy of Dyslipidemia

Saumitra Ray, Srina RayChapter 15e: How to Deal with Complication of Prolonged Antibiotic Therapy

Pushpita MandalChapter 16e: Navigating End-of-life Medical Decisions with Cultural Sensitivity

Reinold OB GansChapter 17e: Osteocalcin: New Frontiers in Diabetes

Sudha Vidyasagar, Avinash HollaChapter 18e: Arterial Blood Gas Analysis: A Rational Approach

SV Ramanamurty, TVSP MurtyChapter 19e: Asthma: New Therapeutic Avenues

Sachin Hosakatti