-

12e

CHAPTERAnemia in Chronic Kidney Disease

Saif Quaiser, Ruhi Khan, Shahzad Faizul Haque

ABSTRACT

Anemia is common in all patients of chronic kidney disease (CKD), which is linked to a lower quality of life as well as a higher risk of morbidity and mortality. The processes underlying anemia linked to CKD are numerous and intricate. A decline in the generation of endogenous erythropoietin (EPO), absolute and/or functional iron deficiency, and inflammation with elevated hepcidin levels are the major contributors to the pathogenesis. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) and oral or intravenous iron supplements are the most frequently used treatments for patients. However, recently there have been some notable developments in the management of CKD-related anemia, which may be practice-defining, which will be discussed in the chapter.

INTRODUCTION

Anemia is a common problem in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). As kidney disease progresses, anemia increases in prevalence, affecting nearly all patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESRD). Anemia in chronic kidney disease is associated with reduced quality of life and increased cardiovascular disease, hospitalizations, cognitive impairment, and mortality and is typically normocytic, normochromic, and hypoproliferative.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2012 guidelines define anemia in adults and children > 15 years with CKD as when the hemoglobin (Hb) concentration is < 13.0 g/dL (< 130 g/L) in males and < 12.0 g/dL (< 120 g/L) in females.

Several studies focused on the prevalence of anemia in dialysis naïve CKD patients and reported variable anemia rates up to 60%. Anemia is more prevalent and severe as the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) declines. The prevalence of anemia also increases with the progression of CKD, from 8.4% at stage 1 to 53.4% at stage 5. NADIR-3 (Study of non-anemic stage 3 CKD patients who develop renal anemia) study revealed that those had developed anemia significantly progressed more rapidly to CKD stages 4–5 and had higher rates of hospitalizations (31.4% vs. 16.1%), major cardiovascular events (16.4% vs. 7.2%), and mortality (10.3% vs. 6.6%).

PATHOGENESIS OF ANEMIA IN CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE

Anemia in CKD is caused by multiple factors. Endogenous erythropoietin (EPO) levels gradually decreasing has traditionally been thought to play a major impact. Other factors, such as an absolute iron deficiency brought on by blood losses or poor iron absorption, an ineffective use of iron stores caused by elevated hepcidin levels, systemic inflammation in CKD and related comorbidities, a decreased response of the bone marrow to EPO because of uremic toxins, a shorter red cell life span, or vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiencies have also been identified as contributing to anemia in CKD patients.

Levels of serum transferrin saturation (TSAT), an indicator of circulating iron, and serum ferritin, an indicator of stored iron, have historically been used to define and diagnose iron deficiency in CKD. Absolute iron deficiency in CKD is defined as TSAT < 20% and ferritin < 100 mg/L in patients who are not receiving hemodialysis therapy [nondialysis-dependent CKD (ND-CKD)] or < 200 mg/L in patients who are receiving hemodialysis [dialysis-dependent CKD (D-CKD)]. TSAT < 20% and ferritin > 100 mg/L in patients who are ND-CKD or > 200 mg/L in patients with D-CKD are the criteria for functional iron deficiency.

The metrics that are currently being utilized to estimate body iron reserves or forecast therapeutic response are unreliable. Additionally, in order to choose the best course of action, it may be clinically useful to differentiate between subgroups of ‘functional iron deficiency’ caused by inflammation or hepcidin-mediated iron sequestration and kinetic iron deficiency from erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA)-stimulated bursts of erythropoiesis.

NEWER IRON DEFICIENCY INDICES

The percentage of hypochromic red blood cells (HRCs) and the reticulocyte hemoglobin content (CHr) are two red blood cell (RBC) measures that have been created and are now more frequently used in various hematological analyzers to address this issue.

Reticulocyte Hb is a functional parameter that can be used to direct iron and ESA therapy since it shows if iron is integrated into reticulocytes within 3–4 days of starting iron administration.

Hypochromic red blood cell is a sensitive long-term, time-averaged functional measure that indicates iron availability over the previous 2–3 months. Instead of estimating the quantity of stored iron, the proportion of HRC and the CHr estimates the Hb content of RBCs. As a result, they are more accurate indicators of functional iron insufficiency and can predict a patient’s response to iron therapy as well as, if not better than, serum iron, TSAT, and ferritin. A meta-analysis done for the 2016 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines revealed that HRC > 6% predicted individuals who would respond to iron (as well as a TSAT < 20% and ferritin < 100 ng/mL). Compared to TSAT and ferritin, percent HRC had a higher negative predictive value. Both percent HRC and CHr can be assessed by flow cytometry.

The thresholds that are used to diagnose iron deficiency are percent HRC > 6% or CHr < 29 pg.

The NICE guidelines, thus, recommend that iron deficiency be diagnosed using HRC or CHr.

Although serum hepcidin level estimation has been studied recently in some studies but till date, it has not been shown to be a reliable indicator of ESA responsiveness in patients with CKD or of the distinction between absolute and functional iron shortage.

HYPOXIA-INDUCIBLE FACTORS

The glycoprotein EPO, which has a molecular weight of 30.4 kDa, interacts with its receptor on the surface of erythroid progenitor cells, which are found mostly in the bone marrow. EPO is an important stimulator of RBC survival, proliferation, and differentiation. In response to variations in tissue oxygen tension, EPO is primarily produced by the fibroblast-like interstitial peritubular cells of the kidneys. The transcription of the EPO gene regulates the synthesis of EPO. The hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) system, whose activity is influenced by tissue oxygen levels, is one of the most significant variables that controls its expression.

The HIF1 binds to the EPO gene and promotes its expression in response to hypoxia or anemic stress. HIF1α and HIF1β are the two parts that makeup HIF1. Under normoxic circumstances, HIF1α is essentially absent but is constitutively expressed. But in conditions of low oxygen tension, HIF1α accumulates and moves to the nucleus where it binds to HIF1β. By attaching to DNA sequences known as hypoxia response elements (HREs), the HIF1α-β heterodimer controls the expression of numerous hypoxia-sensitive genes, either upregulating or downregulating them. This quick adaptive reaction has dual goals of increasing oxygen delivery and reducing oxygen consumption in order to prevent cellular harm. The EPO gene is one of these hypoxia-sensitive genes and when it is activated, more EPO is produced.

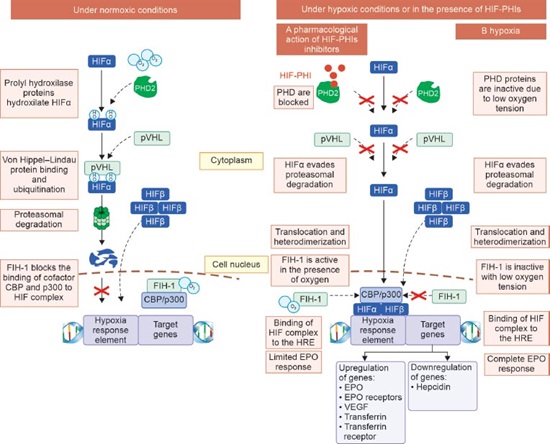

The HIF1α degrades under normoxic environments. HIF1α is hydroxylated twice at the proline residues to do this. Prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes, which are specialized HIF prolyl-hydroxylases, carry out this hydroxylation. These enzymes require the cofactors, oxygen, iron, and 2-oxoglutarate to function. There have been three variants described: PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3. The primary isoform controlling HIF activity is PHD2. After being hydroxylated, HIF1α is bound by the E3 ubiquitin ligase von Hippel Lindau (pVHL), which then targets it for proteasomal destruction. HIF1α can stabilize and go to the nucleus when there is low oxygen tension, which prevents PHDs from acting. The newly developed ‘hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors’ (HIF-PHIs) aim to block this mechanism (Fig. 1).

ROLE OF ERYTHROPOIETIN

Erythropoietin levels in CKD patients are too low in relation to the severity of anemia. EPO deficit begins early in the progression of CKD, although it seems to worsen when eGFR drops below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

FIG. 1: Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) under normoxic conditions, and pharmacological effects of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors (HIF-PHIs) under hypoxic conditions.

(CBP: CREB-binding protein; EPO: erythropoietin; FIH: factor inhibiting HIF; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; HIF-PHI: hypoxia inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor; HRE: hypoxia response element; O2: oxygen; OH: hydroxyl; PHD: prolyl hydroxylase domain protein; pVHL: Von Hippel–Lindau protein; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor)

This absolute EPO shortage may be brought on by errors in EPO sensing as well as a decline in EPO synthesis. CKD is linked to a change in how oxygen is delivered to the kidneys as a result of decreased blood flow. As a result, the renal tissue adapts to use less oxygen, maintaining a normal tissue oxygen gradient in the process. PHD enzymes continue to be active as a result, neither the HIF heterodimer nor the EPO gene are activated.

When normal range EPO levels coexist with low Hb levels in CKD patients, this is known as a functional EPO deficit or EPO resistance, and it shows that the bone marrow response to endogenous and exogenous EPO is impaired in these patients. Proinflammatory cytokines in addition to hepcidin, whose synthesis is increased by inflammation, may also contribute to EPO resistance, because it prevents erythroid progenitor survival and proliferation.

IRON METABOLISM

Iron is necessary for an effective erythropoietic response to EPO, and in anemic situations, treating iron shortage permits using less exogenous EPO. The majority of the iron requirements are met by releasing iron from storage sites and recycling the iron found in senescent erythrocytes.

The amount of iron that is obtained by food intake is significantly less. Additionally, there is no physiological system in place to control iron excretion. It is lost by the desquamation of intestinal epithelial cells, skin cells, and blood losses, and these losses are made up by dietary iron absorption, which is controlled by hepcidin.

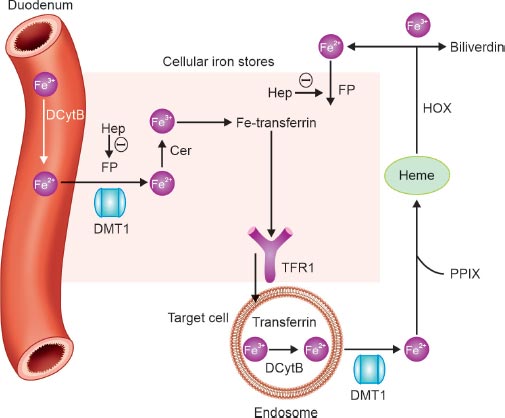

FIG. 2: Iron handling.

Note: Θ represents a negative effect.

(Cer: ceruloplasmin; DCytB: duodenal cytochrome B; DMT1: divalent metal transporter 1; Fe: iron; Hep: hepcidin; HOX: heme oxygenase; FP: ferroportin; PPIX: protoporphyrin IX; TFR: transferrin receptor)

Ferroportin, the only known iron exporter, releases the iron content of macrophages from the phagocytosis of senescent red blood cells, hepatocytes, or enterocytes (dietary iron absorbed in the duodenum). Transferrin then carries iron through the bloodstream and binds to the transferrin receptor to deliver iron to the target cells. The amount of intracellular iron and cell growth control transferrin receptors. The primary regulator of iron metabolism is hepcidin, a liver-produced acute-phase protein that circulates in the blood. Maintaining proper systemic iron levels is its goal. By reducing the expression of the apical divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) in the enterocyte, hepcidin is considered to reduce the absorption of iron in the duodenum. Hepcidin contributes to both iron storage and absorption. Hepcidin does, in fact, encourage the internalization of ferroportin into the cell for its breakdown, preventing iron from leaving enterocytes, macrophages, or other iron reserves and entering the circulation (Fig. 2).

Through erythroferrone (ERFE), EPO inhibits hepcidin production during stressed erythropoiesis. Erythroblasts secrete the hormone ERFE in response to EPO. Also, while HIF-2α increases iron availability by activating the genes encoding DMT1 and duodenal cytochrome b (DCYTB), which are necessary for the transport of dietary iron from the intestinal lumen and for the import of lysosomal iron arising from the circulation, HIF-1α and likely HIF-2α regulate hepcidin production by directly binding to and suppressing its promoter.

CLINICAL APPROACH TO MANAGEMENT

The treatment of anemia in CKD has undergone a significant evolution, starting with the first oral iron supplements (ferrous sulfate) introduced in the 1830s, followed by red blood cell transfusions in the 20th century, the first use of recombinant human EPO (rhuEPO) in the late 1980s, long-acting ESAs, and most recently, the widespread use of intravenous iron supplements. The cornerstone of the management of anemia in CKD patients involves the correction of factors shown in Table 1.

Iron Supplementation

Intravenous (IV) iron has been demonstrated to be more effective at increasing ferritin and Hb levels in CKD stage 5 patients on dialysis (CKD-5D)/non-dialysis dependent (NDD) patients while lowering the need for ESA and transfusions. With the possible exception of the phosphate binder ferric citrate, oral iron preparations are less efficacious in hemodialysis patients. Constipation and digestive intolerance also lower the tolerance and compliance of oral iron formulations.

TABLE 1: Potentially correctable versus noncorrectable factors involved in the anemia of CKD, in addition to ESA deficiency. Easily correctable

Potentially correctable

Diificult to correct

• Absolute iron deficiency

• Vitamin B12/folate deficiency

• Hypothyroidism

• ACE inhibitor/ARB

• Nonadherence

• Infection/inflammation

• Underdialysis

• Hemolysis

• Bleeding

• Hyperparathyroidism

• PRCA

• Hemoglobinopathies

• Bone marrow disorders

(ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB: angiotensin-receptor blocker; CKD: chronic kidney disease; ESA: erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; PRCA: pure red cell aplasia)

Source: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for anemia in chronic kidney disease. Kidney International Supplements. 2012;2(4):281.TABLE 2: Oral iron formulation for treating anemia in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. Iron formulation

Dose prescribed (per tablet)

Elemental iron

Recommended dosage

Traditional oral iron formulations

Ferrous sulfate (generic)

325 mg

65 mg

Three tablets a day

Ferrous fumarate

325 mg

106 mg

Two tablets a day

Ferrous gluconate (fergon)

325 mg

37.5 mg

Five tablets a day

Ferric citrate (auryxia)

1,000 mg

210 mg

Three tablets a day

Novel oral iron formulations

Ferric maltol (ferracru)

30 mg

30 mg

Two tablets a day

Liposomal iron (ferrolip)

30 mg

30 mg

One tablet per day

Sucrosomial iron (sideral forte)

100 mg

30 mg

One tablet per day

Source: Pergola PE, Fishbane S, Ganz T. Novel oral iron therapies for iron deficiency anemia in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019;26(4):272-91.

TABLE 3: Intravenous iron formulations for treating anemia in CKD. Preparation

Concentration of elemental iron (mg/mL)

Maximum single dose

Maximum weekly dose

Minimum injection time for maximum dose

Iron sucrose

20

200 mg

500 mg

2–5 minutes

LMW iron dextran

50

20 mg/kg

–

> 60 minutes

Sodium ferric gluconate

12.5

125 mg

–

10 minutes

Ferric carboxymaltose

50

1,000 mg

1,000 mg

15 minutes

Iron isomaltoside

100

20 mg/kg

20 mg/kg

250 mg/min

(CKD: chronic kidney disease; LMW: low molecular weight)

Source: Schaefer B, Meindl E, Wagner S, Tilg H, Zoller H. Intravenous iron supplementation therapy. Mol Aspects Med. 2020;75:100862.TABLE 4: Different ESAs for treating anemia in CKD. Agent

Route

Half-life in hours (SC, IV)

Dose

First generation epoetin α/β

IV, SC

19, 7

50–100 units/kg administered three times per week

Second generation darbepoetin

IV, SC

49, 25

0.45 µg/kg every week or 0.75 µg/kg every 2 weeks

Third generation methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta

IV, SC

130, 133

0.6 µg/kg administered every 2 weeks

(CKD: chronic kidney disease; ESAs: erythropoiesis-stimulating agents; IV: intravenous; SC: subcutaneous) Both oral and IV iron therapy can be administered to patients who are not on dialysis, according to the 2012 KDIGO guidelines. The NICE recommendations advise giving oral iron to people who are not using ESAs and giving IV iron to people who cannot tolerate oral therapy or who do not meet their goals within 3 months.

Tables 2 and 3 illustrate the different oral and IV iron preparations being used in CKD patients worldwide.

Erythropoiesis-stimulating Agents

Endogenous EPO is a glycoprotein hormone naturally produced by the peritubular cells of the kidney that stimulates red blood cell production in response to low partial pressure of oxygen in an anemic state. ESAs are recombinant versions of EPO produced pharmacologically via recombinant DNA technology in cell cultures.

Epoetin alpha and beta, darbepoetin alpha (DPA), and continuous erythropoietin receptor activator (CERA) are the three generations of ESA, respectively. They have varied pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics, such as differing half-lives and EPO receptor affinities, allowing for less frequent doses and simpler administration for ND-CKD patients using long-acting ESAs as shown in Table 4. Although controversy exists regarding the relative safety and efficacy of various ESA, a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing monthly administration of CERA with reference shorter-acting agents epoetin alpha/beta and DPA, showed noninferiority regarding Hb target achievement, major adverse cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality in CKD patients. Although two landmark trials (CREATE and TREAT) did show improvement in the quality of life of CKD patients, there is still no study which has translated treatment with ESA into significant morbidity/mortality benefit.

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2012 guidelines advocate for adult CKD patients with anemia, not on iron or ESA therapy, a trial of IV iron (or in CKD-ND patients alternatively a 1–3 months trial of oral iron therapy), if an increase in Hb concentration without starting ESA treatment is desired, and TSAT is < 30% and ferritin is < 500 ng/mL (< 500 mg/L). For adult CKD patients on ESA therapy who are not receiving iron supplementation, a trial of IV iron (or in CKD-ND patients alternatively a 1–3 months trial of oral iron therapy) is suggested, if an increase in Hb concentration or a decrease in ESA dose is desired, and TSAT is < 30% and ferritin is < 500 ng/mL (< 500 mg/L).

For adult CKD-5D patients, that ESA therapy should be used to avoid having the Hb concentration fall below 9.0 g/dL (90 g/L) by starting ESA therapy when the Hb is between 9.0–10.0 g/dL (90–100 g/L) with target Hb concentration of not > 11.5 g/dL.

Hypoxia-inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors

In contrast to ESAs, which substitute endogenous EPO, HIF PHIs promote transcription of the EPO gene in the liver and kidneys, increasing the amounts of endogenous EPO. By enhancing intestinal iron absorption and/or reducing iron sequestration, HIF PHIs may also improve the amount of iron that is accessible for erythropoiesis. HIF pathways, however, have a wide range of nonerythropoietic effects and control or interact with many biological processes. Therefore, there is still a theoretical worry that using HIF PHIs for a prolonged period of time may have more hazards than using ESAs in terms of a number of side events, such as cancer, thrombosis, cardiovascular disease, polycystic kidney disease progression, and the advancement of diabetic retinopathy.

Currently, six HIF-PHIs are in clinical development, including daprodustat, desidustat, enarodustat, molidustat, roxadustat, and vadadustat. For patients with ND-CKD and those with incident and prevalent D-CKD, large, randomized trials have shown that roxadustat, vadadustat, and daprodustat are superior to placebo and/or noninferior to ESAs in correcting and/or maintaining Hb at target values as shown in Table 5. Molidustat, enarodustat, and desidustat have shown similar results.

The cardiovascular safety profile of HIF-PHI is comparable to ESAs, but the risk of thrombosis, especially with roxadustat, needs to be addressed in larger RCTs. The information currently available does not support the notion that using HIF-PHIs will lessen the need for intravenous or oral iron supplements in people with ND-CKD or CKD-5D or that they are more effective in treating anemia in conditions of chronic inflammation.

Currently, all three classes of drugs available for the management of anemia in CKD have certain advantages and disadvantages that need to be taken into consideration before prescribing them (Table 6).

FUTURE TRENDS

A dialysate or intravenous solution is used to give the water-soluble iron salt ferric pyrophosphate citrate. Iron is delivered to circulating transferrin directly by ferric pyrophosphate citrate, as opposed to conventional IV iron preparations that are taken up by reticuloendothelial macrophages to liberalize iron. Ferric pyrophosphate citrate has been shown to lower ESA and IV iron requirements while maintaining Hb levels without significantly increasing iron reserves in phase two and three RCTs.

Moreover, inhibitors of hepcidin production or action, which are in development at preclinical and clinical stages and therapies currently used or being investigated in other disease states, for example, interleukin-6 specific antibodies, other anti-inflammatory biologicals, and activin receptor ligand traps are areas of research in the future, which may add to the armamentarium of drugs used to treat anemia in CKD.

TABLE 5: Summary of major HIF-PHI trials. Roxadustat

Vadadustat

Daprodustat

Half-life

12–13 hours

4.5 hours

4 hours

Dosing

Three × weekly

Daily

Daily

Efficacy in ND-CKD

• Superior to placebo in Hb ↑ over 52 weeks (ALPS. OLYMPUS)

• Noninferior to darbepoetin alpha in Hb response (DOLOMITES)

• Superior to darbepoetin alpha in first IV iron use (DOLOMITES)

Noninferior to darbepoetin alpha (PRO2TECT)

• Noninferior to epoetin beta pegol

• Noninferior to darbepoetin alpha in ↑ Hb (ASCEND-ND)

Efficacy in D-CKD

• Noninferior to epoetin alpha in Hb ↑ from baseline (HIMALAYAS)

• Superior to ESA in mean Hb ↑ (PYRENEES, ROCKIES, SIERRAS)

• ↓ IV iron use (PYRENEES)

• ↓ transfusion (SIERRAS)

Noninferior to darbepoetin alpha in maintaining Hb (INNO2VATE)

Noninferior to darbepoetin alpha in ↑ Hb (ASCEND-D)

Safety

• No increased risk for all-cause mortality and MACE in D-CKD (pooled)

• Significantly ↓ MACE and MACE + versus epoetin alpha in D-CKD (pooled)

• ↑ Thromboembolic events in ND-CKD and D-CKD

• Noninferior to darbepoetin alpha in all-cause mortality and MACE in DD-CKD (INNO2VATE)

• Did not meet noninferiority to darbepoetin-alpha in MACE and all-cause mortality in ND-CKD (PRO2TECT)

Noninferior to darbepoetin alpha in first MACE, MACE, or thromboembolic events and MACE or HF hospitalization (ASCEND-ND and ASCEND-D)

(ND-CKD: nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease; D-CKD: dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease; Hb: hemoglobin; HF: heart failure; HIF-PHI: hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor; IV: intravenous; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events) TABLE 6: Potential advantages and disadvantages of various CKD-anemia therapies. Agents

Advantages

Disadvantages

HIF-PHIs

• Oral dosing is more convenient for some patients

• May facilitate anemia treatment in patients with nondialysis-dependent CKD

• May improve the utilization of iron for erythropoiesis, particularly oral iron

• May be more effective in chronic inflammatory states (CRP > 5 mg/L)

• Thrombosis risk

• Difficult to monitor adherence

• Potential polypharmacy and drug–drug interactions

• Less clinical experience

• Potential risk of enhancing tumor growth

• Potential risk of worsening retinopathy

• Potential risk of cyst growth in ADPKD

ESAs

• Adherence can be monitored with in-clinic administration.

• Extensive clinical experience

• Treatment requires self-injection or regular clinic visits.

• Resistance in chronic inflammatory states

• Risk of enhancing tumor growth

• Antibody-mediated pure red cell aplasia

Iron formulations

No serious adverse effects of oral iron

• If taken orally, risk of poor gastrointestinal tolerance and nonadherence to therapy

• If taken intravenously, risk of allergic/anaphylactic reaction, potential risk of increasing oxidative stress, and potential risk of hemosiderosis is rare

(ADPKD: autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESAs: erythropoiesis-stimulating agents; HIF-PHIs: hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors) CONCLUSION

Particularly, the currently utilized Hb, serum TSAT, and serum ferritin measurements are unreliable for calculating body iron reserves or forecasting therapeutic response. Additionally, the best thresholds, targets, and treatment plans for anemia are still unknown, and they have not been adjusted for different disease conditions, age groups, sexes, or the presence of additional comorbidities.

In line with tendencies to individualize therapy across all professions, there is a need to make treatment goals for patients more complicated and precise. The creation and validation of better instruments for identifying ideal, individual anemia correction targets, measuring patient-reported quality of life, and assessing concrete clinical outcomes are crucial for upcoming investigations and are potential areas of research in the future.

The newer oral agents for management of anemia in CKD patients has rekindled a new hope for better and affordable care, safety and efficacy of which will be more evident in the near future.

SUGGESTED READINGS

1. Drüeke TB, Parfrey PS. Summary of the KDIGO guideline on anemia and comment: reading between the (guide)line(s). Kidney Int. 2012;82(9):952-60.

2. Stauffer ME, Fan T. Prevalence of anemia in chronic kidney disease in the United States. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84943.

3. Portolés J, Martín L, Broseta JJ, Cases A. Anemia in chronic kidney disease: From pathophysiology and current treatments, to future agents. Front Med. 2021;8.

4. Mcmurray JJV, Parfrey PS, Adamson JW, Aljama P, Berns JS, Bohlius J, et al. Kidney disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Anemia Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for anemia in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(4):279-335.

5. Stancu S, Bârsan L, Stanciu A, Mircescu G. Can the response to iron therapy be predicted in anemic nondialysis patients with chronic kidney disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(3): 409-16.

6. Fishbane S, Kowalski EA, Imbriano LJ, Maesaka JK. The evaluation of iron status in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(12):2654-7.

7. Urrechaga E, Hoffmann JJML. Assessment of iron-restricted erythropoiesis in chronic renal disease: evaluation of Abbott CELL-DYN Sapphire mean reticulocyte hemoglobin content (MCHr). Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2019;79(6):363-7.

8. Piva E, Brugnara C, Spolaore F, Plebani M. Clinical utility of reticulocyte parameters. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35(1):133-63.

9. Sunder-Plassmann G, Hörl WH. Laboratory diagnosis of anaemia in dialysis patients: use of common laboratory tests. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1997;6(6):566-9.

10. Ratcliffe LEK, Thomas W, Glen J, Padhi S, Pordes BAJ, Wonderling D, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Iron Deficiency in CKD: A Summary of the NICE Guideline Recommendations and their Rationale. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(4):548-58.

11. van der Weerd NC, Grooteman MPC, Nubé MJ, ter Wee PM, Swinkels DW, Gaillard C AJM. Hepcidin in chronic kidney disease: not an anaemia management tool, but promising as a cardiovascular biomarker. Neth J Med. 2015;73(3):108-18.

12. Pan X, Suzuki N, Hirano I, Yamazaki S, Minegishi N, Yamamoto M. Isolation and characterization of renal erythropoietin-producing cells from genetically produced anemia mice. PloS One. 2011;6(10):e25839.

13. Carmeliet P, Dor Y, Herbert JM, Fukumura D, Brusselmans K, Dewerchin M, et al. Role of HIF-1alpha in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 1998;394(6692):485-90.

14. Vogel S, Wottawa M, Farhat K, Zieseniss A, Schnelle M, Le-Huu S, et al. Prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) 2 affects cell migration and F-actin formation via RhoA/rho-associated kinase-dependent cofilin phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(44):33756-63.

15. Eckardt KU. The noblesse of kidney physiology. Kidney Int. 2019;96(6):1250-3.

16. Fehr T, Ammann P, Garzoni D, Korte W, Fierz W, Rickli H, et al. Interpretation of erythropoietin levels in patients with various degrees of renal insufficiency and anemia. Kidney Int. 2004;66(3):1206-11.

17. Wenger RH, Hoogewijs D. Regulated oxygen sensing by protein hydroxylation in renal erythropoietin-producing cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298(6):F1287-96.

18. Dallalio G, Law E, Means RT Jr. Hepcidin inhibits in vitro erythroid colony formation at reduced erythropoietin concentrations. Blood. 2006;107(7):2702-4.

19. Macdougall IC, Bock A, Carrera F, Eckardt KU, Gaillard C, Van Wyck D, et al. The FIND-CKD study:a randomized controlled trial of intravenous iron versus oral iron in non-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients: background and rationale. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(4):843-50.

20. van Swelm RPL, Wetzels JFM, Swinkels DW. The multifaceted role of iron in renal health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(2):77-98.

21. Kautz L, Jung G, Valore EV, Rivella S, Nemeth E, Ganz T. Identification of erythroferrone as an erythroid regulator of iron metabolism. Nat Genet. 2014;46(7):678-84.

22. Peyssonnaux C, Zinkernagel AS, Schuepbach RA, Rankin E, Vaulont S, Haase VH, et al. Regulation of iron homeostasis by the hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs). J Clin Invest. 2007;117(7):1926-32.

23. Frazer DM, Anderson GJ. The regulation of iron transport. BioFactors. 2014;40(2):206-14.

24. Umanath K, Jalal DI, Greco BA, Umeukeje EM, Reisin E, Manley J, et al. Ferric Citrate Reduces Intravenous Iron and Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent Use in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(10):2578-87.

25. Fishbane S, Block GA, Loram L, Neylan J, Pergola PE, Uhlig K, et al. Effects of Ferric Citrate in Patients with Nondialysis-Dependent CKD and Iron Deficiency Anemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(6):1851-8.

26. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2021). Chronic kidney disease: assessment and management. NICE guideline (NG203). [online] Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng203/chapter/Recommendations#correcting-iron-deficiency [Last accessed January, 2024].

27. Pergola PE, Fishbane S, Ganz T. Novel oral iron therapies for iron deficiency anemia in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019;26(4):272-91.

28. Schaefer B, Meindl E, Wagner S, Tilg H, Zoller H. Intravenous iron supplementation therapy. Mol Aspects Med. 2020;75:100862.

29. Jelkmann W. Erythropoietin. Front Horm Res. 2016;47:115-27.

30. Minutolo R, Garofalo C, Chiodini P, Aucella F, Del Vecchio L, Locatelli F, et al. Types of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and risk of end-stage kidney disease and death in patients with non-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;36(2):267-74.

31. Drueke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, Eckardt KU, Macdougall IC, Tsakiris D, et al. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2071-84.

32. Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Eckardt KU, et al. A trial of Darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(21):2019-32.

33. Gupta N, Wish JB. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors: A potential new treatment for anemia in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(6):815-26.

34. Yamamoto H, Nobori K, Matsuda Y, Hayashi Y, Hayasaki T, Akizawa T. Molidustat for renal anemia in nondialysis patients previously treated with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents: A Randomized, Open-Label, Phase 3 Study. Am J Nephrol. 2021;52(10-11):884-93.

35. Provenzano R, Szczech L, Leong R, Saikali KG, Zhong M, Lee TT, et al. efficacy and cardiovascular safety of Roxadustat for treatment of anemia in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD: Pooled Results of Three Randomized Clinical Trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(8):1190-200.

36. Ku E, Del Vecchio L, Eckardt KU, Haase VH, Johansen KL, Nangaku M, et al. Novel Anemia Therapies in Chronic Kidney Disease: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2023;104(4):655-80.

37. Pratt RD, Grimberg S, Zaritsky JJ, Warady BA. Pharmacokinetics of ferric pyrophosphate citrate administered via dialysate and intravenously to pediatric patients on chronic hemodialysis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33(11):2151-9.

38. Gupta A, Lin V, Guss C, Pratt R, Alp Ikizler T, Besarab A. Ferric pyrophosphate citrate administered via dialysate reduces erythropoiesis-stimulating agent use and maintains hemoglobin in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2015;88(5):1187-94.

39. Massy ZA, Drueke TB. Activin receptor IIA ligand trap in chronic kidney disease: 1 drug to prevent 2 complications-or even more? Kidney Int. 2016;89(6):1180-2.

40. Casper C, Chaturvedi S, Munshi N, Wong R, Qi M, Schaffer M, et al. Analysis of Inflammatory and Anemia-Related Biomarkers in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Siltuximab (Anti-IL6 Monoclonal Antibody) in Patients with Multicentric Castleman Disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(19):4294-304.

Home

Home

e-Contents

Chapter 1e: Prosthetic Valve Thrombosis

Harbir Kaur Rao, Rajinder Singh GuptaChapter 2e: Diabesity and Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

Rajiv Awasthi, Avivar AwasthiChapter 4e: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: An Update

Vinay Kumar Meena, Nazim Hussain, Rajani NawalChapter 5e: Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors Beyond Glycemia

Amit VarmaChapter 6e: Intrahepatic Cholestasis

Archith Boloor, Nikhil Kenny ThomasChapter 8e: Tobacco and Chest

Rajbir Singh, Prabhpreet Kaur, BL Bhardwaj, RS BhatiaChapter 9e: Lung Metastasis

RS Bhatia, Prabhpreet Kaur, Rajbir Singh, BL BhardwajChapter 10e: Important Drug Interactions in Clinical Practice

Srirang AbkariChapter 11e: Renal Tubular Acidosis

Surjit TarafdarChapter 12e: Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease

Saif Quaiser, Ruhi Khan, Shahzad Faizul HaqueChapter 14e: Current Positioning of Nonstatin Therapy of Dyslipidemia

Saumitra Ray, Srina RayChapter 15e: How to Deal with Complication of Prolonged Antibiotic Therapy

Pushpita MandalChapter 16e: Navigating End-of-life Medical Decisions with Cultural Sensitivity

Reinold OB GansChapter 17e: Osteocalcin: New Frontiers in Diabetes

Sudha Vidyasagar, Avinash HollaChapter 18e: Arterial Blood Gas Analysis: A Rational Approach

SV Ramanamurty, TVSP MurtyChapter 19e: Asthma: New Therapeutic Avenues

Sachin Hosakatti